The Veterinarian is Complete!

After starting our huge scanning project with Volume one back in January 2016, we can finally celebrate the release online of the 75th and final volume of The Veterinarian, free for everyone to read in its entirety. The Veterinarian ran from 1828 to 1902 and offers a fascinating insight into the changing veterinary thought throughout a century filled with experimentation and invention.

Click here to browse The Veterinarian online!

This celebration would not be possible without the hard and meticulous work of our Archive and Digitisation Assistants, Adele Bush (Jan-Dec 2016), Helena Clarkson (Jan 2017-Sep 2018) and Jayna Hirani (Sep 2018-Nov 2020), who together created around 65,000 scans and over 1000 sheets of metadata, listing every article title and author.

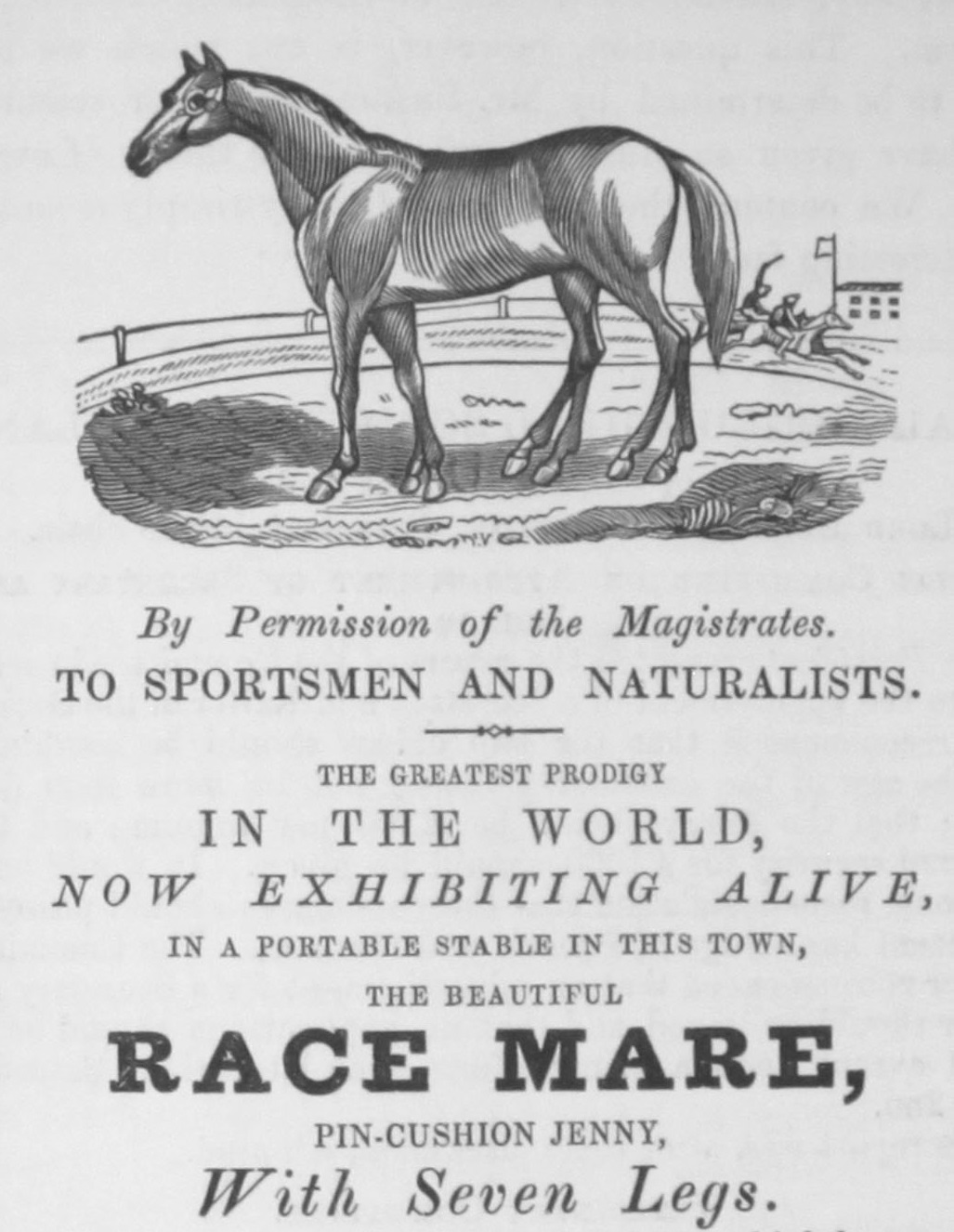

Copy of a handbill promoting ‘Pin-Cushion Jenny’, from The Veterinarian, Vol 60 No 4, April 1887

About The Veterinarian

Since the Vet History project was first proposed by RCVS Knowledge, making The Veterinarian available has been a key priority. Launched in 1828 by William Percivall and later joined by William Youatt, both critics of the London Veterinary School and eager for reform, the journal captures the birth and development of the veterinary profession in Britain and its place within the context of an explosive era of scientific discovery.

The Veterinarian was one of the major organs of discussion, debate and dissemination of new veterinary practice and theory in Britain. Each issue will typically contain accounts of specific veterinary cases, summaries of current knowledge on specific diseases or injuries, news of developments in legislation or national events, reviews of new publications, and reports from the numerous local and national veterinary societies.

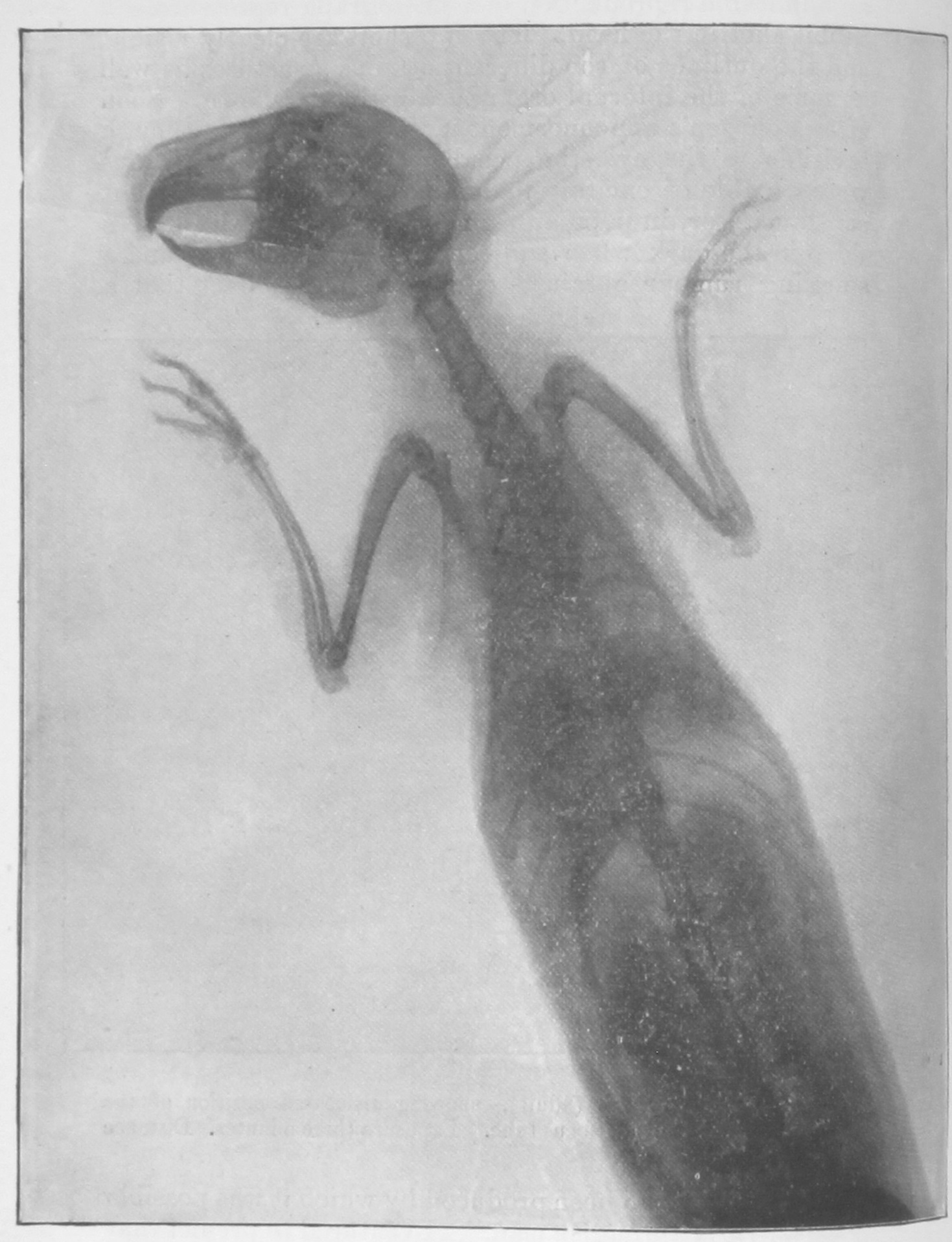

Beyond the strictly veterinary, the journal also covered wider scientific developments of the time. For example, editorials and articles from 1885-1886 discuss the legal implications of Pasteur’s pioneering treatment of rabies, and early examples of ‘Röntgen photographs’ created using X-rays ‘for want of a better title’ were featured in 1897.

‘Röntgen photograph’ of a rabbit, from The Veterinarian, Vol 70 No 5, May 1897

Helping researchers find what they want

The wealth of information contained in this journal covers a very broad range of subjects and includes contributions from many of the most influential veterinary surgeons working in Britain and its colonies. As such, we have worked hard to make sure researchers can easily find and discover articles most relevant to their interests.

Every issue has been digitised individually, and with a full list of contents and article authors. We have also added tags to each issue for specific ailments, anatomy, and organisations. (Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most used tag on Vet History is ‘horse’, with 966 items!)

The most frequently used tags in the Digital Collections

Finally, you can also easily search for content within each issue by using the full-text search in the Universal Viewer.

One of our regular users of the Digital Collections, Sandi Howie, who is working to complete her doctoral thesis on the veterinary community in late nineteenth century Scotland, told us:

The addition of the Veterinarian to Vet History’s Digital Collections, and the keyword search facility, is transformative of historical research. Veterinary historians can for the first time readily access this key source material at any time and from anywhere. As a researcher, I can’t thank the RCVS Knowledge team enough.

A labour of love

The most recent member of the RCVS Knowledge team to take on The Veterinarian digitisation is Jayna Hirani. As the person to finally take this project over the finish line, she was both relieved and sorry to see the project end. The painstaking process of scanning, cropping, converting, uploading, tagging and creating metadata required incredible attention to detail, but also allowed Jayna to really delve into the content and get a comprehensive oversight of the concerns and preoccupations of vets in the late nineteenth century.

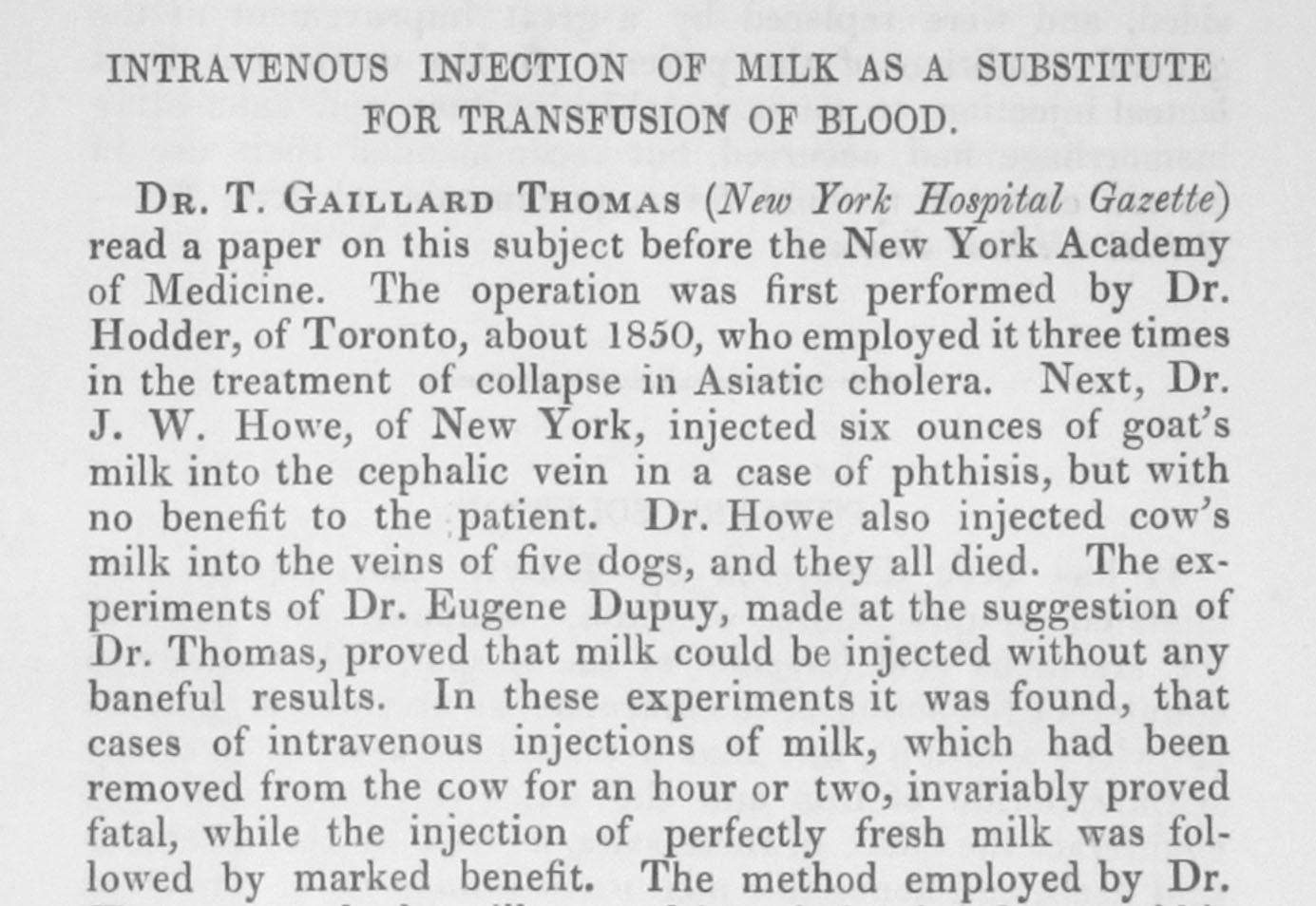

Jayna noticed that the main issue at this time was legitimising the profession, and protecting its reputation from unqualified practitioners, following the Veterinary Surgeons Act 1881. However, another trend was for articles about strange experiments and discoveries about what was and was not scientifically possible – such as transfusing the milk of a cow into the veins of dogs to treat fever and cholera.

Excerpt of article from The Veterinarian, Volume 52 No 1, January 1879

Highlights

Other highlights suggested by Jayna demonstrate the broad variety of the content in the Journal:

An 1872 account of truffle hunting in France, using ‘pig-greyhounds’ and paying them with acorns!

Article from The Veterinarian, Volume 45 No 3, March 1872

An 1890 poem ‘The Doleful Ballad of Germs’ demonstrating that a little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

Poem from The Veterinarian, Volume 63 No 11, November 1890

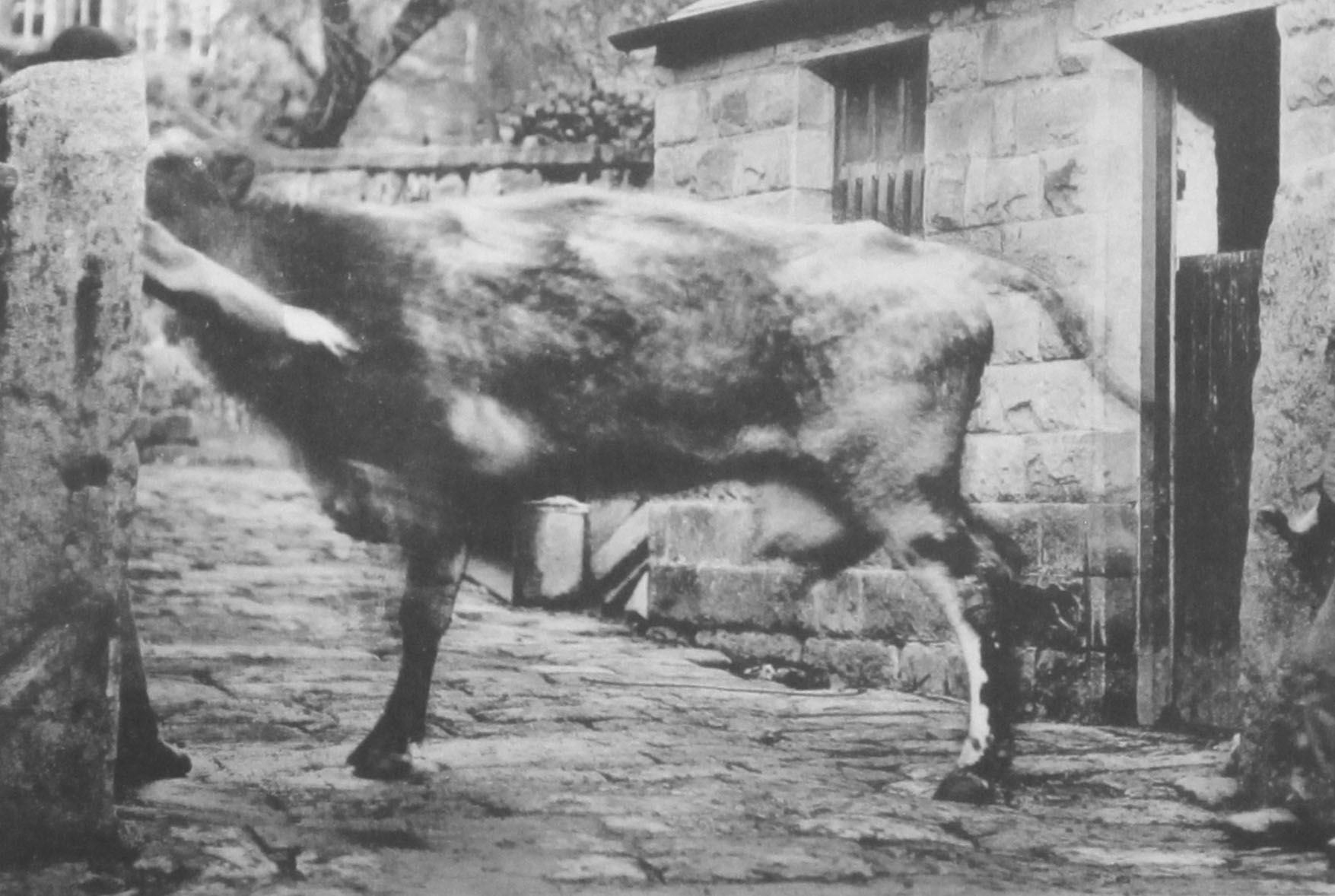

The first photograph to appear in the Veterinarian of an ox afflicted with laminitis.

Photograph from The Veterinarian, Volume 67 No 8, August 1894

Go Explore!

Issues of The Veterinarian received nearly 10,000 views in 2020, so why not explore the journal for yourself and discover articles about every weird and wonderful subject from around the world, captured through the specific lens of nineteenth-century men of letters.

Click here to browse The Veterinarian online