A Welsh veterinary adviser

In honour of St David’s Day, the feast day of the patron saint of Wales, I have decided to look at one of the two Welsh language items that we have in our collection Meddyg y fferm arweinydd i drin a gochel clefydau mewn anifeiliad by James Law which was published in 1881.

I am no Welsh language expert, so a friend has translated the title for me, and her translation leads me to believe that this is a Welsh language version of Law’s The veterinary adviser: being a guide to the prevention and treatment of disease in domestic animals which was first published c1879 running to at least 8 editions.

These English and Welsh versions have a number of features in common: they share a publisher, Thomas Jack of Edinburgh, and their pagination and number of plates and illustrations is the same which would appear to confirm my theory that they are one and the same

As the title suggests the book was intended to be a guide for the farmer to use when they were unable to get advice from a veterinary surgeon. It offers practical veterinary advice on common diseases of domestic animals which the farmer can use instead of consulting a ‘quack’.

The preface of the 8th edition of The veterinary adviser, written in 1896 when Law was working in America and at a time when the American veterinary profession was still in its infancy, expresses the aim of the book rather nicely:

“This work is especially designed to supply the need of the busy American farmer…we have…livestock estimated at $1,500,000,000…affording an almost unlimited field for the…pursuit of veterinary medicine…[yet] livestock is largely at the mercy of ignorant reckless pretenders whose barbarous surgery is only equalled by their reckless and destructive drugging…to give the stock owner such information [to allow] him to dispense with the…services of such pretenders…is the aim of this book”

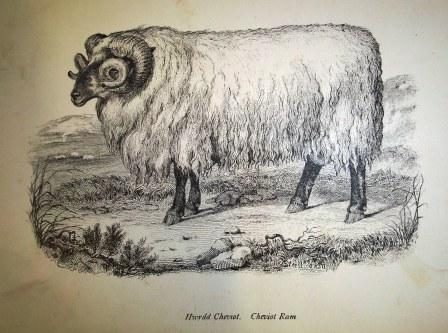

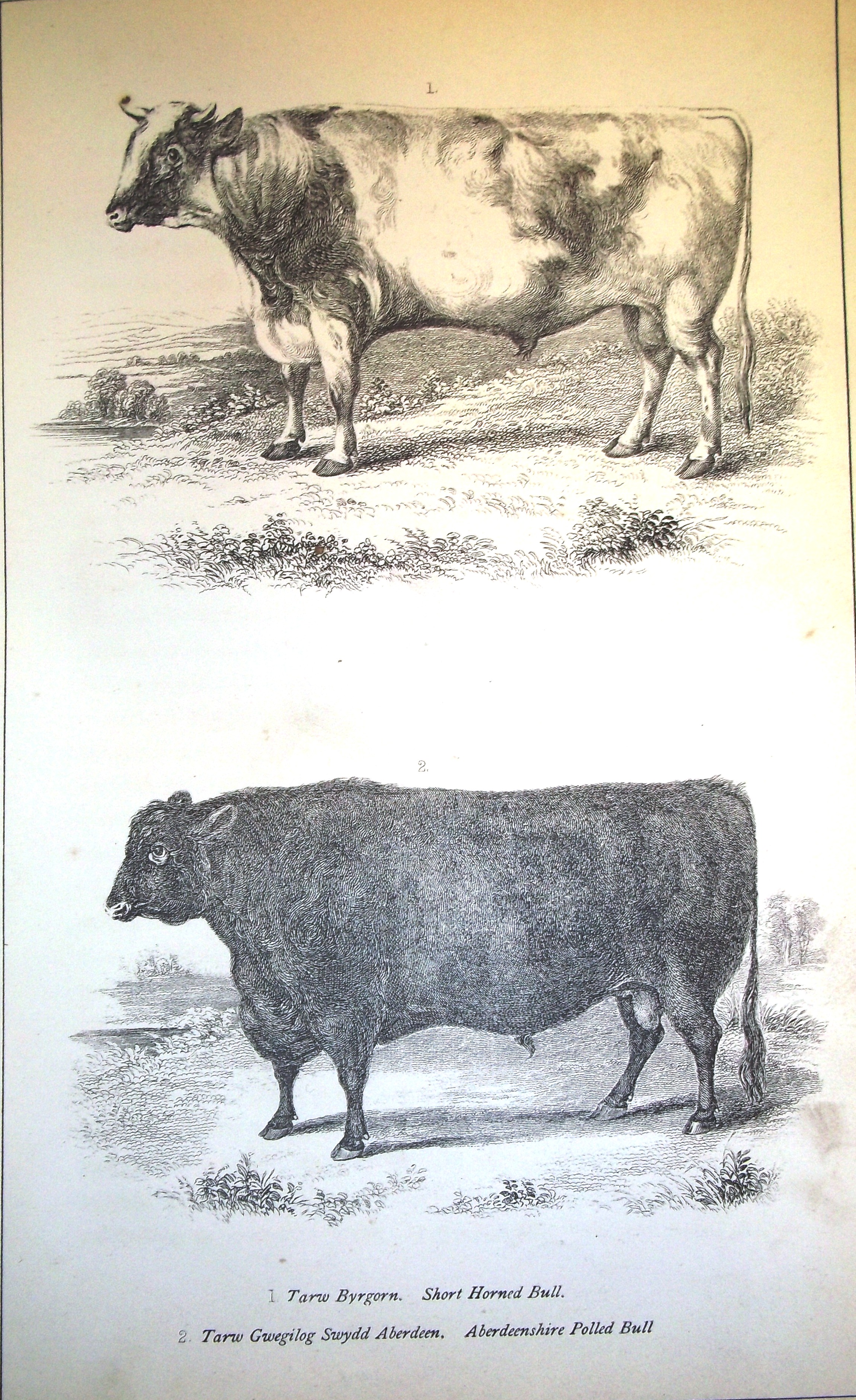

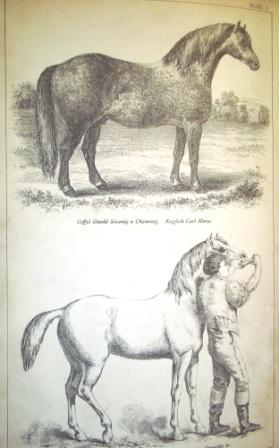

The book also contains 24 full page illustrations showing breeds of livestock, three of which are shown here, and numerous other illustrations within the text.

The author James Law, a 1861 graduate of the Dick Veterinary School in Edinburgh, had a prestigious teaching career in both Scotland and America. Following his graduation he taught at the New Veterinary College Edinburgh with John Gamgee. He was then hired in 1868 by the newly formed Cornell University to teach biology, agriculture and veterinary medicine. It was at Cornell that his later writings, including his 5 volume Textbook of veterinary medicine, took shape.

The inscription in the front of our copy of Meddyg y fferm arweinydd i drin a gochel clefydau mewn anifeiliad indicates that it was owned by a couple named Thomas who lived in Llangyfelach near Swansea. Unfortunately we don’t know anything about them so we can’t say if they actually used the book to help care for their animals.

Dydd Gŵyl Dewi Hapus!