Connie Ford (1912-1998)

In 1970 Connie Ford was awarded an MBE in the New Year’s Honours List in recognition of her long career in the study of disease and infertility in cattle. It was a just reward for her dedication to researching the relationship between animal health and environmental factors such as geology, water quality and mineral intake, as well as acknowledging her skills in communicating her theories. To Ford it may have also served as recognition of the struggles and prejudices she faced, especially in the early years of her career.

Connie Ford was born in Charlton, southeast London in 1912, and graduated from the Royal Veterinary College London in 1933, a time when there were still few women in the profession. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Connie was not from a wealthy background. Indeed, her enrolment in college was made possible thanks to a scholarship from the London County Council (now the Greater London Authority). As she tells a friend in a letter of 12 August 1942 “I scraped through in four years and did without text-books and managed with practically no extra-mural teaching from practitioners, but even so my family’s resources were severely strained”.

Upon graduation, Ford felt that few veterinary practices would welcome a female vet to the team. She tells a friend in a 1941 draft letter “As you may have noticed most of the women [graduates] either marry or set up alone in small animal practice.” She therefore decided to go it alone. Again, without the financial backing of a wealthy family, Ford had to look for other sources of funding to achieve her plan. Fortunately, she was able to acquire a loan from the Connolly Memorial Fund, a charity set up to give financial help to former pupils of the Haberdashers’ Aske’s Hatcham Girls School. This enabled her to purchase premises in New Eltham, not far from her family home.

The practice proved modestly successful, but it seems Ford only ever saw it as a temporary measure. Her main interest was always in agricultural veterinary work. By 1941, having repaid her loan Connie planned to sell her practice and begin a postgraduate DVSM. Unfortunately, the effects of World War Two made finding a buyer difficult, and by the time a sale was finalised her intended course had been cancelled.

Nevertheless, in September 1941 Connie gained a junior research post, at a government laboratory in Wye, Kent. Again, her ambition was soon thwarted. After only nine weeks she was asked to resign. Her supervisor told her she was absent-minded and inaccurate in her work. Any fault of Ford’s is perhaps understandable – over the previous months she had been involved in a serious car accident and her family home had been damaged in an air raid. She had also been caring for her sick father. Indeed, she was dismissed from her role on the day she returned to work after his funeral. All these issues were clearly taking their toll on Connie’s mental health and her work. In a letter of 1st March 1942 looking back on this period Connie refers to “my breakdown”.

A few of Ford’s many field and laboratory notebooks

This dismissal left Connie with little experience in the work she was interest in and no immediate hope of advancement. With no current occupation she enlisted as an Air Raid Precautions ambulance driver in nearby Ashford, but the long periods of inactivity had a negative effect on her health. On her doctor’s advice Ford got herself released from this work and went to recuperate at a friend’s house in Glasgow. It was here that Ford was inspired to join the Women’s Land Army (WLA) and began work on a farm near Dumbarton at the end of March 1942. As well as wanting to help the war effort, Ford had another motive for this choice. She had previously had job applications rejected on the grounds that such physical labour was deemed unsuitable for a woman. As she told a friend in a letter of 7 July 1942, “The fact that I have since served in the WLA for 4 months should stop them from thinking I am still weakly”. Her correspondence from this time shows she thrived in this environment, despite being assigned predominantly arable work. Although the farm she worked on had a dairy herd, the farmer would not allow her to do any of her own research on his cattle.

Having been told by the farmer that she would not be needed after the autumn of 1942, Ford began applying for research roles again. In July 1942 she was accepted for another junior position, this time assisting in the veterinary research laboratory at the Midland Agricultural College at Sutton Bonington, Leicestershire. Although only a temporary position, it finally gave her some useful experience towards her long-term ambitions. There followed a similar temporary position for the Veterinary Investigation Service at the University of Liverpool meaning that by 1944 Ford was gaining both professional achievements and financial stability. In keeping with her socialist principles Ford chose to celebrate her success by helping others and gave a generous donation to the Connolly Memorial Fund which had been so helpful to her in setting up her practice.

Ford returned to the laboratories at Sutton Bonington for much of 1946 and 1947. Then in early 1948 she reached a step closer to her goal when she was offered the position of Assistant Veterinary Investigation Officer at the University of Nottingham School of Agriculture. As part of this role she was sent to Hexham, Northumberland, to undertake research on bovine sterility. She describes this in her correspondence as “…messy work, done on farms in the open air and I love it, though most people can’t think why”. On completion of her course Ford became a regional Sterility Officer, this time at the opposite end of the country, at the Government’s laboratory in Weybridge, Surrey.

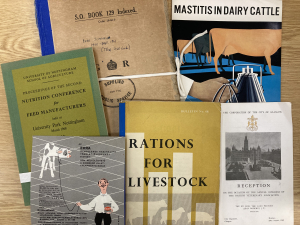

Ford attended many events and collected a multitude of professional papers

It was not until early 1951, ten years after selling her practice, that Ford became a Veterinary Investigation Officer. She was based in the familiar world of Sutton Bonington, with responsibilities across the East Midlands agricultural district. Ford had finally achieved her ambition and would remain in this role until her retirement in 1972. Ford’s archive includes many documents from this time, including her research notebooks. These detail her research into disease and fertility in cattle, and her experiments in adding minerals to their feed. There are also many files concerning specific farms within the East Midlands as she investigates possible links between fertility and environmental factors such as soil type, pasture management and water supply. Additionally, Ford developed her skills at communicating her research. Her paper on Nutritional Factors and Bovine Infertility in the East Midlands was published in the British Veterinary Journal in May 1956, which led to her delivering talks on the subject of links between diet and fertility from 1957 onwards. Her 1964 paper on Infertility in Farm Animals in Britain was also very well received across the profession.

Ford continued to develop her network of contacts, and her correspondence tells us much about the workings of private and public sector agricultural organisations during the mid-Twentieth Century. She was an active member of the British Veterinary Association, the Association of Veterinary Teachers and Research Workers, and the Society for the Study of Animal Breeding. Ford’s archive includes many working papers for each organisation. Similarly, Ford was attending many external events and collected research papers written by her contemporaries, mainly related to fertility and disease prevention in cattle. As such Ford’s collection is a fascinating snapshot of many aspects of the profession in the mid Twentieth Century.

Ford’s choir sang at the 1949 World Festival of Youth and Students in Budapest

Ford retired in 1972 but continued to attend events and conferences until a few months before her death in February 1998, aged 85. Away from her main research Ford also published a biography of Aleen Cust, the first female Member of the RCVS, a work for which the RCVS awarded her the JT Edwards Memorial Medal in 1992. Connie also filled her retirement with many other interests and activities including choral singing, sailing and socialist groups, as well as publishing four volumes of her poetry. In her will Connie left a generous donation to the RCVS to help others training for a veterinary profession.

Connie Ford’s papers have now been fully catalogued and are available for public consultation. Descriptions of these papers can be found on our online catalogue, available here: https://www.rcvsarchives.org/TreeBrowse.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&field=RefNo&key=CF

A further collection of her literary papers is held by the University of Nottingham. Catalogue descriptions available here: https://mss-cat.nottingham.ac.uk/Calmview/Record.aspx?src=CalmView.Catalog&id=CF&pos=1