A not so tall tale

One of the things I love about working in libraries is the weird and wonderful questions you are asked and how, on occasions, information you find for one enquirer can be useful in answering another – sometimes years later.

This has happened to me recently with King George IVs giraffe! In 2010 I found an article in The Veterinarian about this animal for someone who was going to give a talk on the subject – they also wrote about it on the Brighton Royal Pavilion and Museums collections blog.

The giraffe had been given to George, in 1827, by the Viceroy of Egypt, Mohammed Ali (who also gave a giraffe to Charles X of France at the same time) and was kept in the King’s menagerie at Sandpit Gate, Windsor Great Park. Unfortunately the giraffe did not survive that long, dying in 1829, a fact that was satirised in a number of prints that can be seen on the Royal Pavilion and Museums blog.

All of this came back to me when I was doing some research on the RCVS Museum Collection and saw an entry in the museum catalogue of 1891 which read “the trachea of the first giraffe ever brought to England”. I wondered could this be from the famous giraffe that belonged to the King?

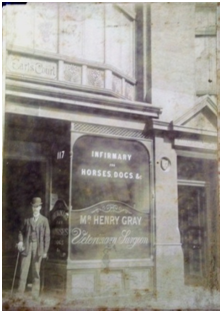

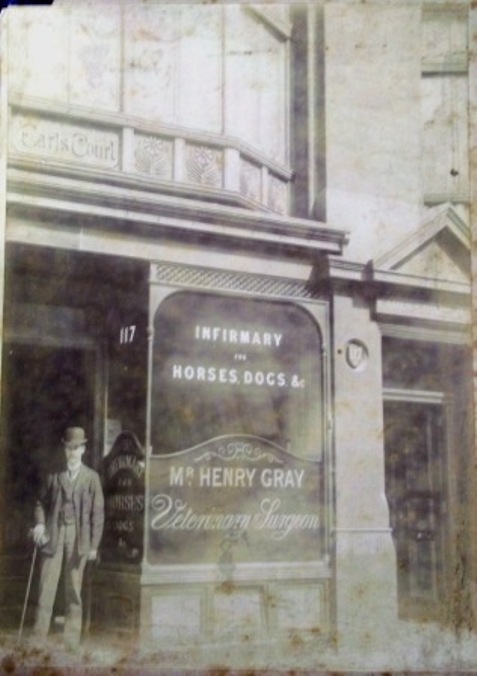

Well the answer is yes it was. The link is the donor of the specimen William J. Goodwin who was an RCVS Council member from 1844-1861, Veterinary Surgeon to Kings George IV and William IV, and Queen Victoria – and the author of the article in The Veterinarian

The article contains information on the health of George’s giraffe in particular as well as more general information on an animal that most readers of The Veterinarian at that time would not have encountered.

Speaking of the giraffe kept at Sandpit gate Goodwin writes:

Unfortunately it’s health did not improve

And it remained small in stature

Sir Everard Home had also spent time with George’s animal and wrote about the tongue of a giraffe in volume 5 of his Lectures on comparative anatomy (p244-250) which was published in 1828.

In spite of all the pain the giraffe must have suffered Goodwin is able to write of its gentle nature

Perhaps a more fitting way to remember this creature than the one portrayed in the satirical illustrations?

Reference

GOODWIN, W.J. (1830), ‘An account of the giraffe: which lately died at Sandpit Gate.’ The Veterinarian Vol. 3 No. 26 pp. 216-219

Images

Image of giraffes in Belfast Zoo © Copyright Kenneth Allen from the Geograph website and licensed for reuse under this Creative Commons Licence

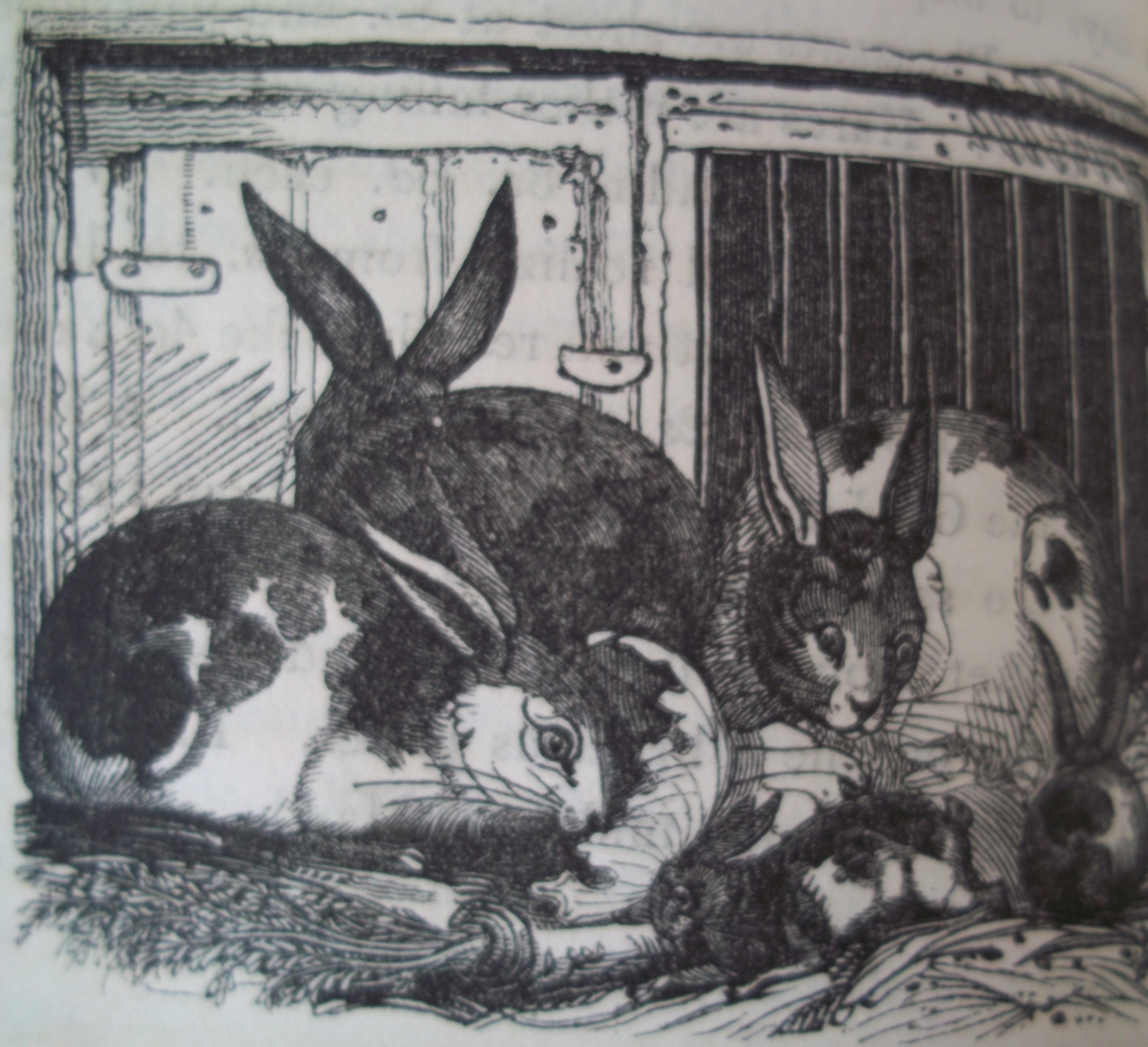

Extracts from The Veterinarian Vol. 3 No. 26 pp. 216-219