This month marks the 75th anniversary of ‘Operation Compass’ which took place in the North African desert, in western Egypt during World War 2. It was here, on 11 December 1940, that a member of the veterinary profession was recognised for gallantry of the highest order.

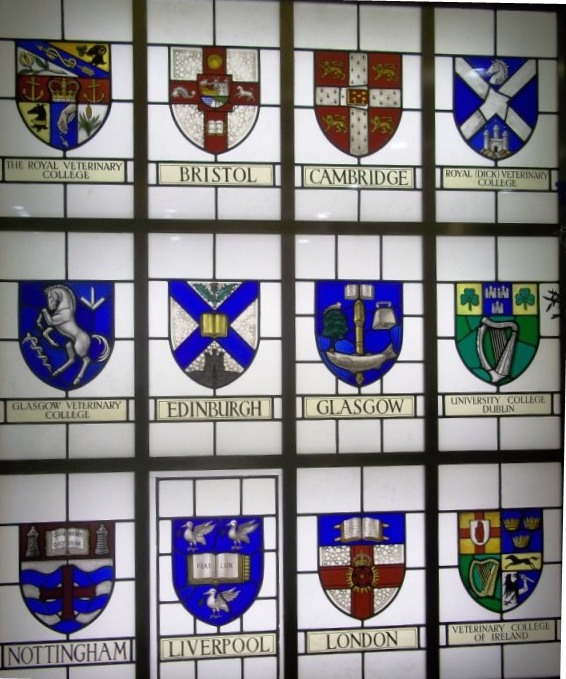

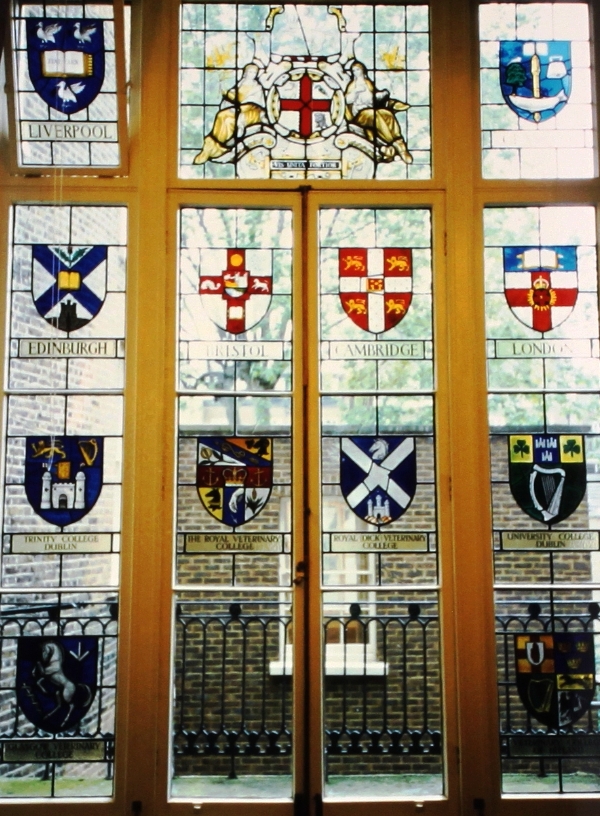

Dr Thomas Somerville was born in March 1887 in Ceylon, the son of a successful tea planter and merchant. After attending Framlingham College Suffolk, he entered the Royal Veterinary College in 1904, graduating MRCVS in 1908. He immediately gained a place at the London Hospital Medical College, believing that a dual qualification would aid his plans to work abroad.

Somerville passed the conjoint medical examination (MRCS, LRCP) in the summer of 1914 and, at the outbreak of war, was commissioned in the Royal Army Medical Corps. He served in France throughout the war: in January 1916 he was awarded the Military Cross (MC) for ‘distinguished action in the field’, and in 1918 received a bar to the MC ‘for conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty.’

Captain T V Somerville c1918

Following the armistice in 1918 he was posted to Northern Russia where he worked as a medical officer on hospital trains, caring for the casualties of the Russian Civil War. He was awarded an OBE in 1920 for this service.

After demobilisation from the army, Somerville pursued a career in medicine, rather than veterinary medicine, working in general practice, initially near to Whitely Bay, Northumberland and then in Bournemouth.

At the outbreak of World War 2, Somerville, aged 52, volunteered for military service. He was commissioned in September 1939 and posted as Medical Officer to the 3rd (Kings Own) Hussars the following month. The 3rd Hussars were despatched to Egypt in the summer of 1940, arriving in Cairo in September, to serve as part of the 7th Armoured Division, the ‘Desert Rats.’

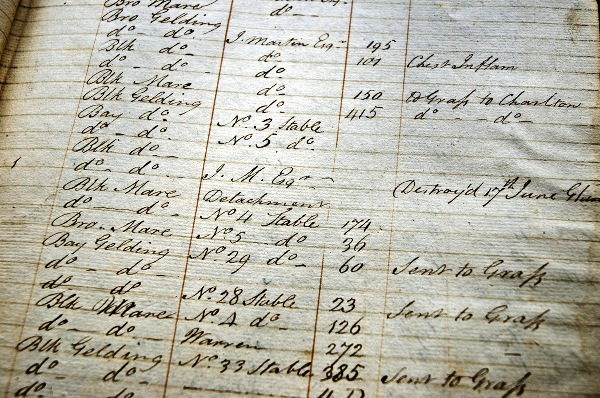

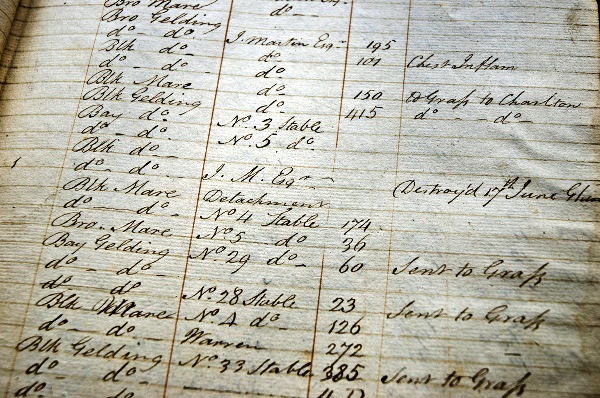

Somerville quickly realised that medical officers would need to be highly mobile in order to provide treatment swiftly. With ‘light-hearted support’ from senior officers, and using a captured Italian ambulance, he designed a vehicle which would allow treatment of casualties on the battlefield. The Medical Assistance Vehicle (MAV) was effectively a mobile surgical unit. Being lightly armed, it could not display a Red Cross, instead Somerville emblazoned the regimental emblem, the Horse of Hanover, on each side.

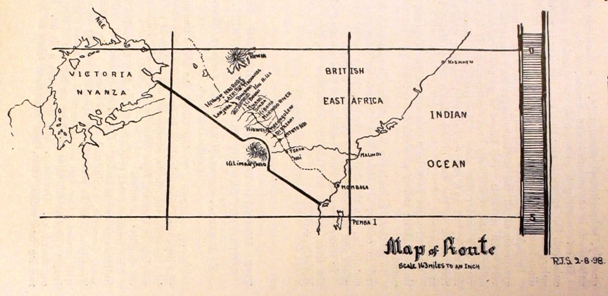

‘Operation Compass’ commenced on 8 December 1940, with allied forces attacking Italian troops at Sidi Barrani The Italians soon withdrew, and the 3rd Hussars were ordered to pursue the retreating forces. On 11 December the tanks of the 3rd Hussars became trapped in the soft crust of the dried salt lakes at Ras El Saida. – they were ‘sitting ducks’ for the Italian artillery.

Somerville drove out onto the battlefield to rescue the injured. A tank commander recalled how he was trapped in a tank, unable to get out and thought he was going to die, when:

“Suddenly this officer appeared from nowhere. I didn’t know who he was. He tried to pull me out but he couldn’t. High explosive shells were coming in at a terrific rate. I told him to get away before we got hit again but he just dived into the turret head first, just his legs sticking out. He came out and pulled at me again. This time I popped out and he dragged me down the side of the tank onto the ground. I was nearly passing out but he sat me up and told me I was going to lose my leg but I could make it if I could hang on. I didn’t know much about it but I learned after that he was Captain Somerville and he took my leg off in that vehicle and saved my life.”

Somerville’s actions that day were clearly described in the citation for gallantry:

“…Capt. Somerville went out among the tanks attending to the wounded regardless of the heavy fire and with no consideration for his personal safety. He continued to attend to and bring in the wounded until all were under cover from the main enemy position, and thereafter he dressed them in a position where they were still unavoidably under fire from snipers. His cool gallantry was an inspiration to others who assisted him, and the means of saving many lives. I consider that in view of the shattering fire of the enemy Capt. Somerville has earned the highest decoration for valour.”

Somerville’s Headstone Suda Bay, Crete

He was recommended for the award of the Victoria Cross (VC). This was agreed at all levels of command until it reached the Commander-in-Chief in February 1941,- Wavell crossed through the recommendation of VC and approved the award of the Distinguished Service Order.

In May 1941 Somerville was posted to Crete where he provided medical care to those injured in the fierce fighting following the invasion by German paratroopers earlier that month. At the end of May he was ordered to retreat, but remained on the island to treat casualties. He, along with his batman Corporal Fred Marlow, was befriended by local partisans, and lived in the hills and mountains during the summer of 1941. During this period Somerville was taken ill; he died on 23 November 1941 and was buried in a local cemetery lying between a local soldier and a local woman. At the end of the war, he was reburied at the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Suda Bay, Crete.

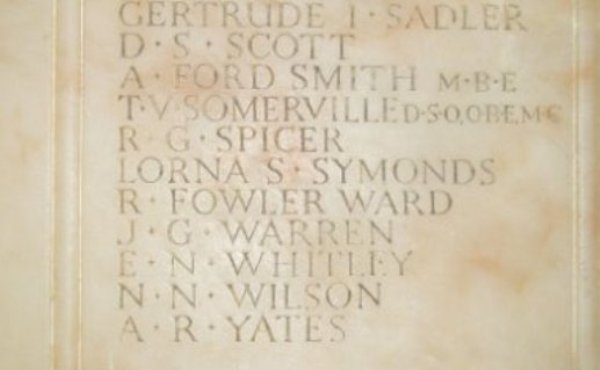

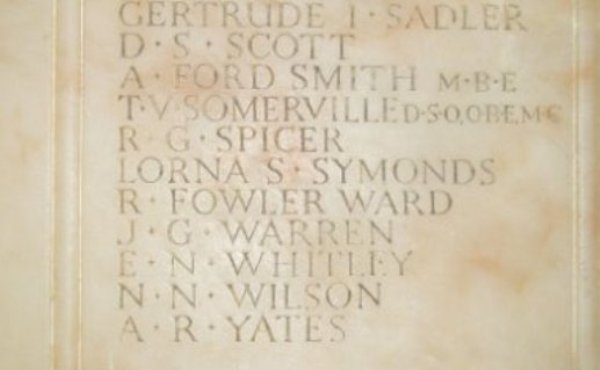

Thomas Somerville is recognised on a number of memorials in this country, including Framlingham, the London Hospital and The Roll of Honour of the Royal College of Surgeons of England; he is yet to be recognised by any veterinary institution.

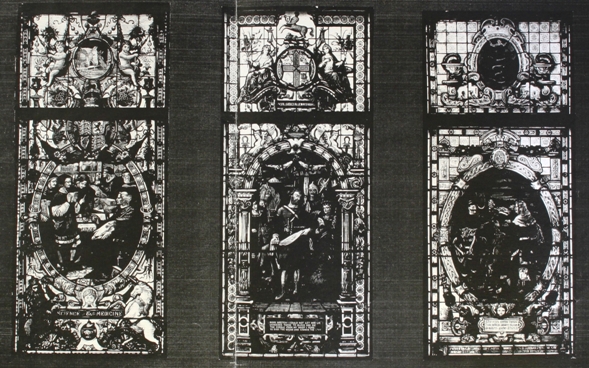

Detail from War Memorial of the London Hospital

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Paul Watkins MRCVS for his help in compiling this post.